“Give me a second. I know this. Hold on. Uuugghh! It’s on the tip of my tongue. I know it but I can’t explain it.”

Have you ever heard something like this from your students? It is frustrating for students and for teachers.

Here is another scenario. You’ve finished teaching the lesson, you’ve reviewed with the students, and they seem to know the material. You give a test. The students perform poorly on the test and complain the test was too hard or worse yet, the test was unfair.

You are frustrated, students are upset, and you might even get a couple of parent emails.

This experience is actually a legit phenomenon. The bad news is that kids are tricking themselves. The good news is there is something you can do about it.

Teachers assess student knowledge and understanding on a regular basis to make sure students are learning. Students also assess their own understanding, but their assessment is flawed. Every time a student hears information about the topic he is learning, he decides if he “knows it” or not. If he thinks he “knows it”, he will not spend excess energy trying to pay attention to something he believes he already knows. The standard by which he determines whether he “knows it” or not is whether or not he has heard this information before.

Students don’t intentionally trick themselves, but it happens all the time.

The Problem

When students think they understand a word, an idea, a concept, etc., they are less engaged. Meaning, they check out more frequently during instruction, practice, review, etc. because they believe they already know it.

The sneaky culprit behind this trickery is familiarity.

Here is how this works. You begin teaching a new unit. A student in your class hears some brand new information.

For example, you’ve just introduced a new novel and provided author information and some background about the time period of the book. You reference some books that students have heard of before, that have influenced this author or have been written in a similar style as this author. There is some familiarity for students. You intentionally do what you can to activate prior knowledge so students have something to connect the new information to.

Later in the week, you decide to play a game so you put your students in groups for a little competition and you ask questions about the content you taught. Kids can talk in their teams and then provide an answer. Students hear the content again from other students. This may be the second or third time they have heard this information in the past week. Here is where the brain tricks them. Students begin to believe they know the information because it is familiar to them.

Some of the students are answering questions correctly, and as a whole class it appears they are ready for a quiz. You give a quiz the following day and students are now required to independently recall and articulate the information. They tank on the quiz and you are both surprised and frustrated. They believed they knew it because it was familiar but they did not truly understand it. The proof is they could not articulate the information.

A True Test of Understanding

The true test of understanding is the ability to independently recall and articulate understanding either verbally or in writing. Familiarity is not the same as real understanding. In fact, familiarity gets in the way of true understanding. This is how students trick themselves into thinking they understand content when they don’t.

The inability to articulate what we think we know in our head is really just a reflection of what we truly understand–not a whole lot about the topic. –Tara Kassi

The problem is that our students trick themselves into thinking they know more than they do.

How do we bypass the familiarity trap and help kids show what they really know? Teachers have to teach not only the academic content, but also strategies for students to accurately assess their understanding.

You can easily incorporate some simple strategies that will help students bypass the “familiarity trap” and help them understand—not just think they understand. In fact, you are probably using many of these strategies now. With new awareness and just a few tweaks, you can use your strategies more effectively and more powerfully. If you need some more strategies check out this post.

5 Strategies for Bypassing the Familiarity Trap:

- Teach students how familiarity tricks their brain. Help them understand how familiarity gives them a feeling of knowing more than they actually know. Teach them how to accurately assess what they know. The way a student can demonstrate he truly understands is to independently recall and explain information out loud. If he can’t do it, he doesn’t know it.

- Partner students with a study buddy to ask each other questions about the material. Explaining answers out loud is important to demonstrate to the student whether or not she can recall the information independently. Make sure students ask each other questions about information that is important, not just the information they are familiar with. You can generate a list of questions with the whole class before you let them break off into partners.

- Create study guides for students. When creating study guides, make sure to include the most important concepts. Students will be drawn to the information they are familiar with, not the new concepts and ideas that are unfamiliar. This is why it is not a good idea to have students create their own study guides unless you have explicitly taught them how to create a study guide.

- Use images or symbols to explain words or concepts. When students use images that make sense to them, those images help them develop a mental image of the concept, idea, or word. Mental images make it easier to explain even the most complex concepts.

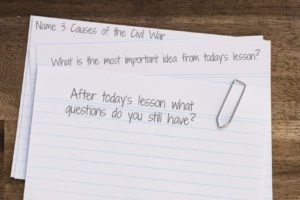

- Use entrance and exit tickets that require students to independently recall information, a concept, or a process. Ask students to complete a “short write” (1-2 sentences) or solve a problem, etc. at the beginning of class. Ask them a question about the content from the day before and have them respond independently in writing.

The next time you think you really know something, test yourself. Explain the idea or concept out loud or in writing. You will know pretty quickly if you really know what you think you know or if you are just fooling yourself.